On May 30th 2024, I caught Olúwatómisìn (Tómisìn) Olúkòsì in a twenty-minute conversation on the state of the Nigerian art sector. Drawing on her wealth of experience in arts administration, we touched on a range of topics, from labour welfare to Nigeria’s relationship with the West, and non-negotiable advice for emerging practitioners. Despite echoing a lot of the uncertainties currently plaguing Nigerians, Tómisìn maintained a hopeful and lighthearted resilience endemic within the country’s youth population.

Please note that the conversation below has been edited.

Tọ̀míwá Adégbọlá (TA): What are your thoughts on the current state of the Nigerian art sector?

Tómisìn Olúkòsì (TO): I have mixed feelings. It’s difficult not to be discouraged by the Nigerian situation and its inadvertent effects on all sectors including our own. But I’m also optimistic because of the young talent that we have – the young, passionate and very strong-willed crop of emerging talent in our industry. It’s the practitioners who have, I think, been through more than enough in this country and are quite determined to make a change in our own generation. I like to think about Lagos Biennial as one of my case studies for why I’m optimistic about Nigeria. With all that didn’t go as well as it could have, the show of solidarity and goodwill was so powerful that it felt like everybody had a stake and was willing to show up, to show their support for the industry. That’s one of the scenarios where I can’t help but be optimistic about the industry.

TA: These things that you’ve described, passion, and that rebellion, in a sense, to right the things that people felt they were wronged by, do you think they are enough?

TO: It’s not enough. [pause] It’s not enough. Over and above everything else, funding, I think, is very conspicuously absent or misallocated. Maybe not misallocated, just, funding doesn’t always go where it’s needed in our industry. And that’s easily the biggest gap. We need funding. We need advocacy. We need stakeholders inside the community to be visibly invested. We need collectors to know that their job doesn’t end with buying art. We need curators to know that their job is to tell our story in the bigger picture, in the – what do you call it? Longue durée. I’m going to spell that out for you. It’s a fancy word I learned. It’s French.

[Shared laughter]

Honestly? We need practitioners to be progressive in their thinking and in their storytelling, in the way that they present our culture. We need to also stop looking to the West for validation, for approval, acceptance. We need to stop looking to the West for trends. We need to stop looking to the West to legitimise the ways that we want to do things. We need a lot. Can I have a day or two to like, itemise what we need? [More laughter] But no, it’s not enough.

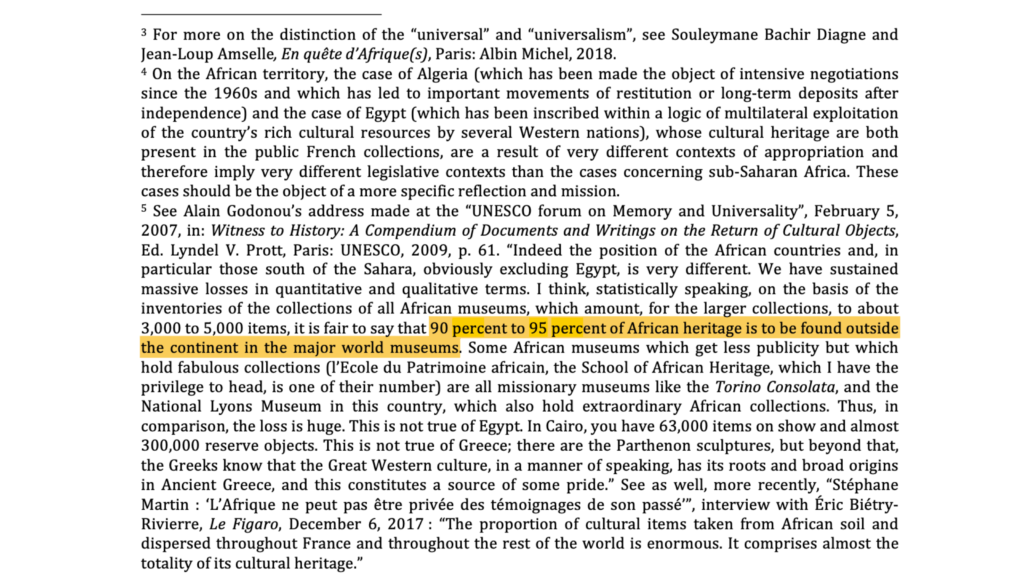

TA: I agree, we need a lot. One point that stuck out was not looking to the West for validation. I am currently researching an article titled ‘When We See Ourselves: How do we value arts without the West?’ So this is something I really want to delve into. Based on where you’ve worked, the experience you have, the conversations you’re having – be honest – is there African arts without the West?

TO: That’s a difficult conversation because a lot of the places we have to look to for our own history are Western, or at least Western-influenced. And we live in an increasingly globalised world. You can’t exactly ‘de-Westernise’, you know, our collective gaze.

Well, you can. We can try. Hence this industry-wide buzzword, “decolonize”. Is it possible soon? No. Is it possible in the future? Ah, I shouldn’t say no.

[More shared laughter]

TO [continued]: Hey! Is it possible? The cynical me says no, it’s not possible today, it’s not possible ever. But, I think it is possible to try, and within that active effort to refresh the ways that we think about our own culture we’ll arrive at something that is a little more, if nothing else, conscious of the ways that external influences have impacted our storytelling and our relationship with our own culture. So, yeah, we might not be able to, you know, remove ourselves and remove that Western perspective from all of our art and culture. But we can educate and dig deeper and look more to the continent. Or when we search for identity, we at least know to look within rather than without.

TA: OK, next question. Do you have any advice for young artists, practitioners, enthusiasts, or anyone who’s basically looking at where you are from the outside and aspires to be in a similar position or take up similar space in the industry?

TO: Go and learn tech. Go and learn tech.

[Laughter]

TO [continued]: You’re probably more qualified than you think for the positions that you think about. In my experience, the people who are capable of self-reflection enough to question whether or not they’re qualified for an opening are usually the most qualified people, but they underestimate their own skills and their own capabilities. So I would say shoot your shot regardless of how far you think you are from where you want to go. Just apply for the job, apply for the open call, and put together the proposal. Also, networking is really important. Just being in the room with the right set of people. Introduce yourself to people and tell them who you are and where you’re going and opportunities will find you that way.

TA: Speaking from experience, that’s great advice. Being open to learning is important as well. I agree with the point that if you’re self-aware enough to reflect and have doubts –

TO: You’re precisely the right kind of person.

TA: And it just means you have that extra capacity to really improve and that’s the main thing, isn’t it? To be willing to grow… doubt is a terrible, terrible thing.

TO: Say less.

[Laughter]

TA: My final question. What are your aspirations for the future of Nigerian art?

TO: I would like to see more – I’ve used this word before – formalised arrangements, institutions, and establishments in the industry. Sometimes it feels like we’re winging it collectively in the Lagos art scene and I don’t think that’s good enough for the level of success that we’ve attained in such a short time. I also think that we’re not doing nearly enough to provide protection for artists, for creatives. What’s the word?

TA: Safeguards.

TO: Yes, safeguards for our own institutions, our own people and the tools that help potential buyers know that this industry is credible.

TA: Better local accreditation.

TO: Yes. Local accreditation. We need to find practical ways to formalise our industry so that we can take stock of our intrinsic value and really take each other seriously. I also want to see the national art scene grow at the same pace that the Lagos art scene is growing because a lot of the commercial success that Nigeria has known didn’t always come from Lagos. It came from Zaria. It came from Osogbo. It came from Oyo, Benin. So we really need to widen the scope of who we consider and where we look for talent in this country. It can’t just be Lagos. What else? What else? What else? The future… People should stop being shady. I want a more transparent industry. I want artists and creatives to feel safe. I want cultural heritage workers to be better compensated. I want to see unions. I want to see unions everywhere. I want people working in heritage management to know what health insurance is. That’s it.

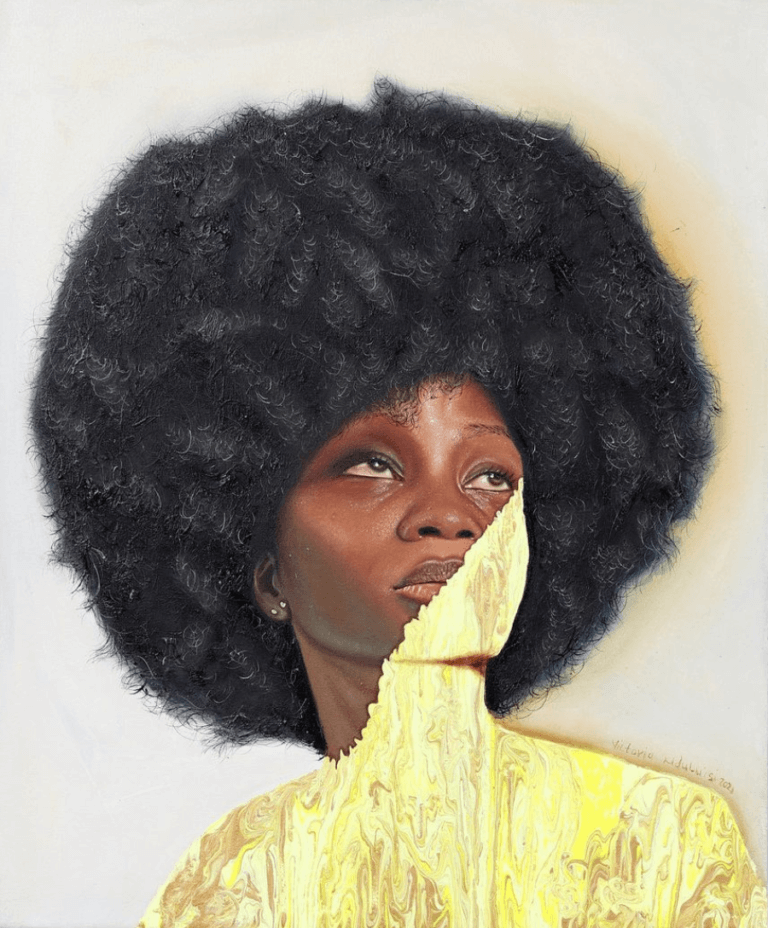

About Tómisìn Olúkòsì

Tómisìn Olúkòsì is a part-time Art Guide Africa contributor and full-time Communications and Development Coordinator for Guest Artists Space Foundation. With a BSc in Architecture and an MSc in Environmental Design from the University of Lagos, she has dedicated the last five years to building capacity within the Lagos commercial and non-profit art sectors. Her specialisms include curatorial writing, SEO copywriting, and grant-winning proposal writing. For more about Tómisìn, click here.